"About that music festival I've been thinking of—You know how they talk about April in Paris? Well, I think we should call it June in Buffalo. Yeah, why not?" — Morton Feldman*

June in Buffalo is an international festival that attracts some of the most widely-renowned artists from across the world. But it is first and foremost a festival in Buffalo, and there is perhaps no ensemble more firmly and proudly Buffalo than the city's orchestra. Founded in 1935, the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra has been one of the city's most important cultural institutions for eighty years. The orchestra has become an integral part of June in Buffalo, concluding the festival each year with its Sunday afternoon concert of new orchestral compositions.

The BPO was founded shortly before the Great Depression, during which it was supported by funds from the Works Progress Administration and Emergency Relief Bureau. Over the years, the orchestra has had some of the most significant artists of the twentieth century serve as music director, including William Steinberg, Josef Krips, Lukas Foss, Michael Tilson Thomas, Maximiano Valdez, Semyon Bychkov and Julius Rudel. Always actively recording, the orchestra has released a number of significant LPs over the years, including the world premiere recording of Shostakovich's Symphony No. 7 "Leningrad" in 1946. In 1977, under the direction of Michael Tilson Thomas, BPO recorded a successful LP titled Gershwin on Broadway. The recording made such an impact on Woody Allen, that the director used several of the LP's selections in the soundtrack to his 1979 film, Manhattan. Under the current direction of JoAnn Falletta, the orchestra has released thirty-two CDs, including a Grammy-winning recording of John Corigliano's Mr. Tambourine Man: Seven Poems of Bob Dylan (2003).

The BPO was founded shortly before the Great Depression, during which it was supported by funds from the Works Progress Administration and Emergency Relief Bureau. Over the years, the orchestra has had some of the most significant artists of the twentieth century serve as music director, including William Steinberg, Josef Krips, Lukas Foss, Michael Tilson Thomas, Maximiano Valdez, Semyon Bychkov and Julius Rudel. Always actively recording, the orchestra has released a number of significant LPs over the years, including the world premiere recording of Shostakovich's Symphony No. 7 "Leningrad" in 1946. In 1977, under the direction of Michael Tilson Thomas, BPO recorded a successful LP titled Gershwin on Broadway. The recording made such an impact on Woody Allen, that the director used several of the LP's selections in the soundtrack to his 1979 film, Manhattan. Under the current direction of JoAnn Falletta, the orchestra has released thirty-two CDs, including a Grammy-winning recording of John Corigliano's Mr. Tambourine Man: Seven Poems of Bob Dylan (2003). |

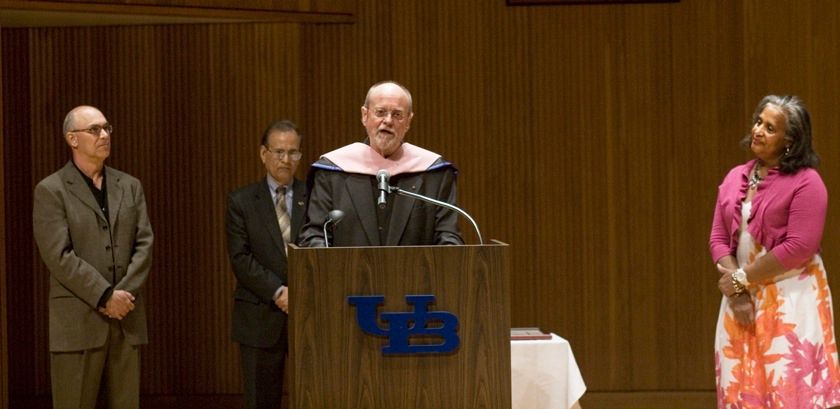

| Lukas Foss |

The orchestra has always had a close relationship with its city. At the 2012 Spring for Music festival at Carnegie Hall, the BPO broke the record for hometown fan attendance. From 1992-96, JiB artistic director, David Felder was the orchestra's Meet the Composer Composer-in-Residence. During these years, the Buffalo-based composer wrote a number of new orchestral works for the BPO, including Three Pieces for Orchestra, composed for the ensemble's 60th anniversary. [The first of these pieces, Linebacker Music, was composed in the midst of the early-1990s Buffalo Bills string of successes—a Buffalo composer writing a piece for a Buffalo orchestra, about the city's most beloved pastime].

|

| Charles Ives |

|

| Eliot Fisk plays Beaser's Guitar Concerto with the BPO at JiB 2012 |

The BPO has a long history with June in Buffalo, and the festival has seen a number of significant performances by the orchestra. One memorable concert took place at JiB 1997, at which the BPO played Feldman's 'Cello and Orchestra (1972), Edgard Varèse's Octandre (1923), and Charles Wuorinen's River of Light. Notably, this program featured Jonathan Golove (of this year's Performance Institute faculty) playing Feldman's wistful 'cello concerto, and Wuorinen himself conducting his orchestral ballet. The year before that, the orchestra played a program featuring Felder's Three Pieces, Donald Erb's Solstice, and Toru Takemitsu's Requiem. The latter piece, composed forty years earlier, was performed in memory of its composer, who passed away earlier that year. This concert was echoed a decade later at JiB 2009, when the BPO reprised the program, substituting Takemitsu's piece with a related memorial work by their former director: Lukas Foss's For Tōru (1996) for flute and orchestra. Other significant performances of recent years have included a 2012 program which included Felder's dynamic Incendio, Fred Lerhdahl's Cross-Currents, Steven Stucky's Jeu de Timbres, and Robert Beaser's Guitar Concerto, which featured a moving performance by world-renowned guitarist Eliot Fisk.

|

| BPO Associate Conductor, Stefan Sanders |

—Ethan Hayden

*Quoted in Renée Levine Packer, This Life of Sounds: Evenings for New Music in Buffalo (Oxford University Press, 2010), 143.